COVID-19 disparities persist in our most vulnerable communities, including low-income families and racial and ethnic minorities, partly because of the financial necessity to continue working, as well as the lack of employment opportunities that enable their residents to work remotely. They are more likely to be essential workers, and that increases their exposure to the virus.

Evidence from subways in NYC

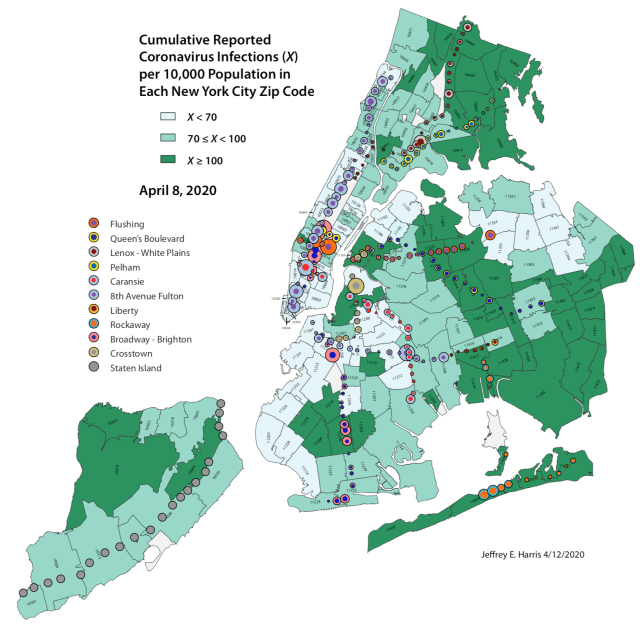

Jeffrey Harris exposed how the subways seeded the massive coronavirus epidemic in New York City in a working paper published by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER).

Harris discovered that “subway lines with the largest drop in ridership during the second and third weeks of March had the lowest subsequent rates of infection in the zip codes traversed by their routes. Maps of subway station turnstile entries, superimposed upon zip code-level maps of reported coronavirus incidence, are strongly consistent with subway-facilitated disease propagation.”

Essential workers living in the Bronx still had to travel on the subway into work each day, exposing themselves to great risk in transit and in the workplace, at a time when many others in higher-income areas of NYC had the privilege to work from home and avoid risking exposure to coronavirus.

Evidence from EHRs in England

Similar to the US, racial minorities and the poor in England are carrying more of the burden from COVID-19. I am deeply impressed by Ben Goldacre’s leadership of a rapid UK response making giant leaps in technology infrastructure to learn in real time from patient experiences using electronic health records (EHR). They formed a public-private partnership called the The OpenSAFELY Collaborative and developed a secure data analytics platform for EHR in the NHS to enable a data-driven response to the COVID-19 pandemic. All of their research analysis code is publicly available on GitHub. In contrast to this controversial study out of thin air, this EHR analysis is legit.

Goldacre’s team learned that compared to white people, Black people in England are much more likely to die from COVID-19, even after controlling for underlying health conditions and lots of other risk factors (hazard ratio [HR] 1.71; 95% CI: 1.44-2.02. Previous research had suggested that the racial disparity was attributable to higher prevalence of obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease, but this study from the OpenSAFELY Collaborative found solid evidence that underlying health explains only part of the disparity.

The research team also examined the relationship between deprivation index (aka poverty or socioeconomic status) and risk of death from COVID-19. They found that patients who were the most deprived (bottom 20%) were nearly twice as likely to die from COVID than the least deprived (top 20%) of adults (hazard ratio [HR] 1.75; 95% CI: 1.60-1.91).

The combined effect of being poor and being black creates a disproportionately high risk of death from COVID-19. My hypothesis is that the disproportionate burden on poor and minority communities is related to higher levels of exposure to the virus, resulting in an increased risk of infection in the first place.

Disparity in risk of exposure

I shared some of my thoughts about COVID-19 racial disparities in an interview with Maggie Smith from the American Journal of Managed Care (AJMC) focused on how protecting the health of our most vulnerable populations requires understanding of motivations. The full transcript available here from AJMC. Here is a clip.

*Casual nerd background and choices were made before understanding this interview was for VIDEO and not just written content.

As time goes on, we’ll learn from academic studies that use mobility data (e.g., SafeGraph and the COVID-19 Mobility Data Network) to reveal who in society had the privilege to stay home and protect themselves and who did not. This is where creatively designed econometric difference-in-difference studies, like the NYC subway study by Jeffrey Harris described above, are essential.

One theory to explore in the future is differences in household size and average number of people per room. Self-isolation of an infectious case is challenging for six people in a two-room apartment. When the number of people per household or cluster of people per square foot is high and many are working outside the home, then the risk of exposure and infection is compounded.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Ms. Smith for her thoughtful interview questions and the opportunity to focus on the disproportionate COVID-19 burden experienced by racial and ethnic minorities in the US.

Header Image Credit: Harris JE. The Subways Seeded the Massive Coronavirus Epidemic in New York City. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 27021, Updated April 24, 2020.